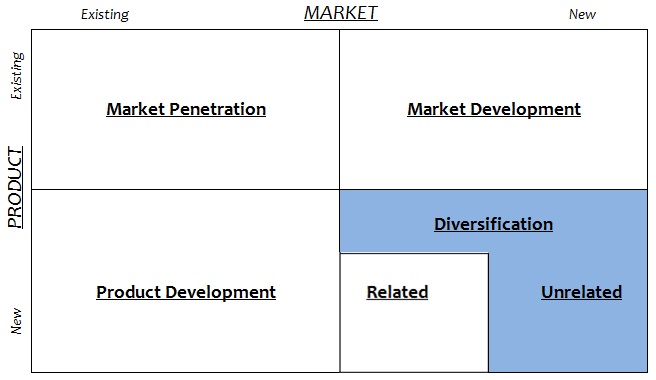

If somebody was to ask what industry Virgin operates in primarily, the first thought that comes to mind would inevitably vary between each of us. This is due to the Virgin Group partaking in what’s known as ‘unrelated diversification’ – the fifth strategy in Ansoff’s Matrix. Unrelated diversification involves entering an entirely new industry that lacks any important similarities with the firm’s existing industry or industries, and is often accomplished through a merger or acquisition.

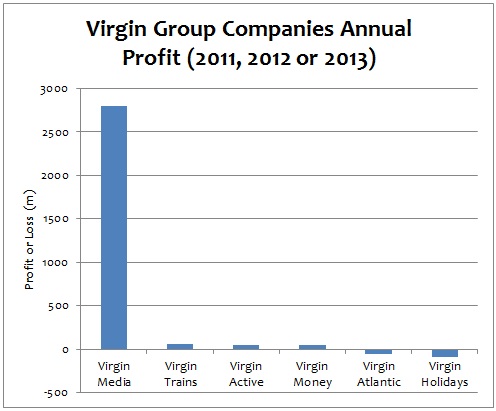

In the case of Virgin, unrelated diversification has certainly been a successful strategy in terms of maximising profitability. Looking back to 1970s and the start of its operations as a record mail order company and record store soon after, given the rapidly changing nature of the music industry since, it is possible that the company would no longer exist if it hadn’t innovated in this way. With a total of 35 subsidiary companies within the Virgin Group globally, within the UK today’s breadwinners look very different to the 1970s, helping the Virgin Group to a total revenue of £15 billion in 2012:

The key to successful unrelated diversification is identifying an industry with strong profit potential, where the firm has internal competences that helps to gain a competitive advantage. Virgin Atlantic’s market entry in the 1980s in a good example of this at a time when great customer service was a rare quality in the airline industry, which was instead plagued by cancelled flights, delays and lost baggage. Virgin’s internal competence of providing an excellent customer experience throughout its existing family of companies offered an advantage that would be hard for competitor airlines to replicate – and therefore potential to charge a price premium.

However, the ‘unrelated diversification’ strategy is far from full proof and there are numerous examples in which it has failed for Virgin. Perhaps the most high profile case is the short rise and rapid fall of Virgin Cola in the mid-1990s – following an ambitious, yet unsuccessful plan to compete with Coca-Cola and Pepsi. Despite the ever-growing fizzy-drinks market, conditions were not conducive to Virgin’s entry due to the existing players’ ability to block access to widespread distribution and a backlash in advertising spend – which ultimately limited Virgin Cola to just a 3% market share on its home UK turf before exiting.

Looking beyond the risk of failure, I would also argue that unrelated diversification creates further risks in terms of losing brand strength, by blurring the delivery of a single strong message. Virgin used to have the image of being a rebellious brand that resonated strongly with its young audiences through music and records – a lifestyle in itself almost – but with Virgin Money and Virgin Trains, it doesn’t have that single message and association any more. Today, the host of sub-brands do not comfortably fit together in a way that Virgin can define itself as meaning something, which goes a long way towards explaining why Virgin isn’t a leader in any of its industries. In the airline, broadband and gym industries to name just a few, Virgin is simply another player and fails to innovate in the way that a leader generally does. Instead, Virgin tends to take an existing service or product and undercut prices or offers a slight variation on the business model.

Richard Branson summarises the Virgin Group’s modern strategy with the quote; “Business opportunities are like buses, there’s always another coming along”. Essentially, Virgin now examines existing industries to see if the group can offer something better than existing companies which may have become complacent – trains, insurance and banking for example.

Virgin has lost some of its magic and, consequently, the brand name survives on its credentials as a strong global business that creates efficiency and profitability where others fail, rather than something more powerful in people’s minds.

With this in mind, a case could be argued that Richard Branson is now attempting to revisit the past and recreate a more distinctive image, such as through the publicity generated around the launch of Virgin Galactic, which aims to launch the first commercial spaceflight. Although this industry is full of uncertainly and offers no commercial value as yet, it brings with it beneficial associations of innovation for the Virgin brand. The diverse nature of the Virgin Group’s business model means that trying to reinforce a niche differentiator of ‘rebellion’ no longer washes for such a broad target audience, so being considered the driving force in an infant industry that holds strong media interest can reach out to all existing audiences; demonstrating that the Virgin brand is always trying to push existing boundaries of possibility.

The next 10 years or so will be a crucial period for Virgin, and it will be interesting to see how it pans out. What will come to mind when somebody says Virgin to us in 2024? Let’s hope it’s much clearer and consistent than it is today.

Pingback: Coca-Cola: Ansoff Matrix | the Marketing Agenda

Pingback: Business Lessons: Richard Branson | the Marketing Agenda

Pingback: Virgin Mobile and Social Media Marketing – Yumna.DICE

Pingback: Can the Online Casino Industry Teach Business Longevity? - The European Business Review