If asked to think of a television advertisement using a ‘fear appeal’, what comes to mind? There’s a strong likelihood that you’re now thinking of a high-fear anti-smoking or “always wear a seatbelt” campaign. More subtly however, everyday consumer products from toothpastes to cleaning products now employ low-fear appeals which are proving to positively influence our behaviour and drive sales.

A fear appeal in advertising involves presenting a risk of using or not using a specific product, service or idea such that if you don’t “buy”, some dire consequence will occur. Low-fear appeals rely on anxiety (an emotional response) being triggered which motivates the audience to take the recommended action to remove the threat – just like wearing a seatbelt can prevent the high-fear of death in a road accident:

The origins of low-fear appeals in consumer product advertising can be attributed to Listerine’s 1920s advertising campaign in which a market for mouthwash was essentially created from nothing. At the time of airing, the average person bathed once a week, never put on deodorant and body odours were accepted as part of life. However, the story of the ad centred around Jane, a beautiful young lady who was at risk of never getting married for the simple reason of bad breath (medically termed, ‘halitosis’) – therefore portraying the offense as unpardonable. The makers of Listerine did not make a mouthwash so much as they made halitosis:

And the results were staggering; within seven years of the original campaign launch, Listerine’s revenues rose from $115,000 to $8 million.

The Theory:

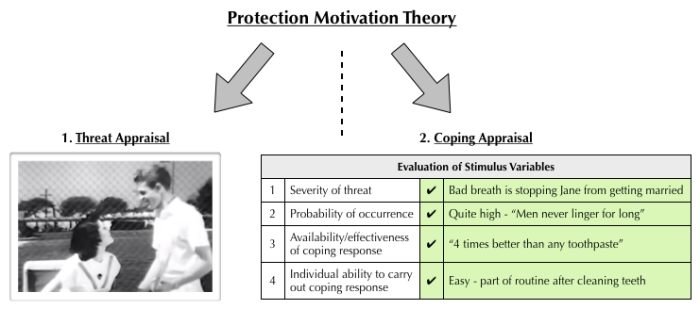

So how do fear appeals influence consumers? Rogers’ Protection Motivation Theory (1975) provides one explanation. The premise of the Protection Motivation Theory is that people are motivated to protect themselves from physical, psychological and social threats. When faced with a new threat (the fear appeal), this initiates a coping appraisal based on four variables; the severity of the threat, probability of the threat occurring if no adaptive behaviour is performed, availability of a coping response (solution), and the individual’s ability to carry out the coping behaviour.

Using the Listerine example, it is clear to see how the advert successfully meets these four criteria in order to motivate consumers to act (buy the product):

The growth of fear appeals for everyday products can be justified by Evans et al.’s study in 2004 which found that, whilst high-fear appeals such as the “always wear a seatbelt” campaign created more anxiety than low-fear appeals, low-fear appeals still caused more anxiety than positive appeals, such as humour. Occupational psychologist, Gorkan Ahmetoglue, explains this is the case because people are more motivated by fear or losing something than the good of gaining something.

A prime example of this growth is the cleaning product industry. In the 1980s, your typical household cleaner advert centred around cleanliness and showed a relaxed approach to keeping ourselves and our homes clean:

But fast-forward 30 years and the notion that we are constantly at risk of infection dominates with fear appeals used to bombard consumers with messages that germs are the evil to be purged at all costs, using buzzwords such as “antibacterial”:

Whilst seemingly very simple for advertisers to employ and obtain a positive response from consumers, fear appeals should be approached with caution as their success is far from full proof. Interestingly, a 2013 meta-analysis by the University of Illinois found that fear appeals can often fail when it comes to repeated behaviours, such as dieting, and are more effective for one-time-only behaviours, including health screenings. Furthermore, in a 1970 edition of the Journal of Marketing, Stuteville suggested that fear appeals are also less effective if the audience has a psychological investment in the product – hence why cleaning products have cashed in!

Pingback: UX Propaganda: Psychological Techniques to Make Your Product Addictive | BLUESTORM

Pingback: UX Propaganda: Psychological Techniques to Make Your Product Addictive | Ethinos

Pingback: Advertising Creates Fear – How Do You and Your Kids React? – Spiritual Meditations

Pingback: Writing by Design | Fear-based Marketing Tactics: Do they work and are they ethical?